As an academic, I published 10 peer-reviewed articles in political science, 2 books, a special journal issue, countless op-ed’s & commentaries, and a popular blog about replication.

How did I do it, alongside teaching, admin, and having two kids?

Here’s my round-up of my 10 most impactful lessons during my 10 years in academia.

You’ll learn how to:

- handle co-authorship strategically

- manage ‘love projects’ versus ‘career projects’

- how you can apply these systems to your own writing life

And you’ll also hear my one mistake that destroyed my system and led to my exit from academia to start my own business (a win win in the end).

Let’s dive in!

# 1 Co-Authoring for speed

Only two articles of my list of publications were written solo — the rest was co-authored. I found amazing collaborators who were often much better at doing statistics, and we split up responsibilities. Here’s why that worked:

- We held each other accountable and got our papers to the finish line, beating isolation and procrastination

- I used branched out from my core research agenda into adjacent topics by working with collaborators who were experts in these other fields

- We brought our ideas together, bridged the literatures in unique ways, and came up with something “new enough” to get published in peer-reviewed journals

Over to you:

Using this collaborative approach to publications, who could you bring on board to create accountability and innovate your ideas?

# 2 Pipeline diversity

I split up my time between ‘career projects’ and ‘love projects.

‘Career projects’ were topics where my collaborators had the data already collected. They could quickly do the statistics and in the meantime, I worked on the theory and story telling (I knew statistics and taught it, but I was a much better story teller). We would use our strengths, work in parallel, and create fast-paced papers for our CVs and career progression.

Having those fast papers in the pipeline then allowed me to invest months and years into ‘love projects’. For example, digging into messy, complicated data collection projects such as big data in human rights, or finding and verifying data on corruption in Brazil. Human rights violations and corruption are notoriously hard to measure, and while I loved those topics, those papers wouldn’t come fast.

Over to you:

Where can you diversify your projects so that you always have one or two fast and effective publications in the pipeline, and work on your real passion on the side?

# 3 Spreading mentors across fields and countries

I had mentors within and outside my University — those from my student times in Germany and the U.S., who supported me for years and kept writing recommendation letters when I was on the job market (I ended up getting two prestigious jobs: a post-doc at the University of Cambridge, and a permanent lectureship at the University of Nottingham).

My mentors kept encouraging me when dozens of applications were rejected. They built me up when I was shortlisted, then dropped. And I even learned from them: statistics, how to apply for grants, getting into conferences.

Some of these mentors were younger than me. Most of them were in other countries. Everyone brought something different to the table, and I’m grateful to this day, even now that I’ve left academia.

How did I get those mentors?

- I went on a course or summer school with them and stayed in touch, asking if I can help them, and hoping they’d support me in return

- Many of them were actively seeking out ambitious students to support, and I grabbed opportunities and volunteering (e.g. I ran a lecture seris on human rights within the Amnesty International student group, and one of the professors who gave a talk co-edited a book from those lectures with me)

- I overcome my imposter syndrome and asked for help when I couldn’t solve a problem (most academics love to help and support)

Over to you:

Is there a mentor you’d love to connect with? What’s holding you back from emailing them to connect?

# 4 Conference backdoor hack

After getting rejected at the big conferences in my field year after year, I realised it’s better to propose a 4-person-panel rather than trying to submit a paper.

So I started asking around in my field if anyone was interested in submitting a panel together. I was often a “junior” panel co-organiser or discussant alongside an eminent professor. I did lots of admin work, but their visibility put me on the radar with an international audience of experts. Being the youngest and least experienced academic on such panels helped me network and become visible. (And I later returned the favour to early career researchers myself).

Over to you:

If you’ve been getting rejected from conferences in your field — could you offer organisation, admin, and run a panel, discussion, or other engagement to put yourself on the radar?

# 5 Handling collaborations without perfectionism

I had collaborations with senior, same-level and junior academics, and I enjoyed all these roles.

My biggest learning was this: I had to accept that sometimes it’s best to let your collaborator do it “their” way, rather than forcing my perfectionism or “my way” onto them. Otherwise, this would have meant delaying submission.

And to be honest, often it didn’t matter in the end if we told presented an argument in a certain way, or if our tables or figures looked exactly the way I would have done them. If the substance was good, the journal editors and peer-reviewers would guide us in the direction they preferred.

Over to you:

How are your co-authorships going? Are you constantly annoyed that the ‘other’ person is not doing it well enough? Do you collaborate with the right people so that you can let go when needed? Or do they push your buttons (perhaps it’s time to find new collaborators)?

# 6 Finding dedicated editors who believe in you

My first paper was based on my 5-year-long PhD work, and I put two more years into getting it published. In hindsight, perhaps I should have tried to publish my PhD as a monograph, but I wanted a paper as soon as possible to prove that I can do it.

I also thought it would be faster to write a paper versus a book (that was not the case for me!).

In went through four rounds of revisions at my dream journal. And the only reason this paper got published in the end is that the editor believed in me (Shareen Hertel) and the topic. I was resilient and determined to grind, again, and again, and again. I never forgot how this person kept giving me yet another chance to improve my paper.

Incidentally, we kept bumping into each other at conferences, and we later even co-authored an article. I’ll be forever grateful.

Over to you:

Do you know any journal editors who tend to publish your topics? Is there any way you can build a relationship with them? This is not to say that you can weasle your way in with a bad paper, but if someone feels invested in you and your topic, grab the opportunity.

# 7 Visiting scholar stints for the soul

I was a visiting scholar twice (at Berkeley, and in Berlin) and invited a visitor to my University (from Brazil). Those were the happiest academic experiences I had, period.

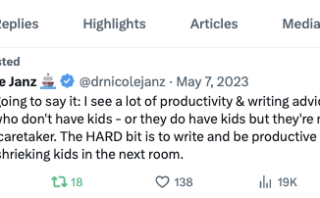

I spent those times writing up papers, writing grants, and enjoying a new environment where I felt no pressure to teach or do admin. I did take along my young kids and had to organise childcare or work limited hours. But it was worth it and gave me much-needed sense of freedom and empowerment. (This changed later.)

# 8 Blogging in a ‘side field’ to build a network I loved

I wrote a blog on a niche subject at the time (Political Science Replication Blog) and got a lot of attention for my engagement, including invites to join and shape international networks for replication and reproducibility such as the UK Reproducibility Network, Project TIER at Haverford College, and others. Those folks were engaged and fun, and lifted me up.

Based on my blog and the relationships in reproducibility that I built, I got grants, wrote papers about the topic, and engaged with altruistic social scientists who believed in better data, training and transparency.

Those papers often counted ‘less’ on my CV, because they engaged with how science is done, rather than presenting breakthrough discoveries.

But the topic got me far more invites, attention, appreciation, and fun times than my actual research agenda of foreign investment and human rights. I always found that odd, and also sad, because for the job market and promotion you need a published paper record, and my replication initiatives counted ‘less’ . But I was so happy to have found the replication folks, many of whom became friends who stayed with me even after I left academia.

Over to you:

What (science-adjacent) theme or networks would you join if you allowed yourself a bit of space, fun, and human connection? And what unexpected benefits might appear for you, if you went for it?

# 9 Small mistakes I made, costing me time

I also made mistakes. I was too perfectionist and tried to do everything “textbook” style. For example, when my data was patchy (corruption and human rights has lots of missing data in cross-country studies), I realised only too late that there’s a limit of what you can publish with such small sample sizes.

I even delayed the submission of my PhD for a whole year because the statistics didn’t work out the way I had hoped. I wasted too much time refining and double-checking my analyses, hoping I can make them ‘look’ like results in textbooks.

Finally, after a lot of pain, writer’s block, and feeling like a failure, I allowed myself to submit “the best I could do with what I had” — and got through the viva (defence) with minor corrections. I’m now much better at avoiding over-editing work and wrote more about it here.

Over to you:

Where are you wasting effort and time for minimum return? Are there limiting beliefs that hold you back? Where could you let go just a little and see if a minimum viable version of your project is good enough?

# 10 My one big mistake: Burning out

To keep a long story short, a few things disillusioned me about my tenured academic ‘dream’ job.

After my second child, the regular commute (2.5h one-way) to campus became a struggle. I took over a leading committee role and taught at least one new courses every year. With promotion as my main goal, I worked harder and harder to prove myself. And when I got exhausted, I fell into the trap of thinking I can ‘outwork’ my exhaustion.

Admittedly, I still thrived when I taught my students and mentored them with their dissertations and procrastination struggles. But my anxiety and overwhelm eventually spiralled out of control.

Soon enough, academic burnout hit and I eventually quit.

I realised that my biggest skills of ‘empathy’ and ‘human connection’ were often suppressed during my academic career. Being overwhelmed and overworked, I couldn’t emotionally detach from rejection, feeling I’m falling behind after having kids, or being unable to go to all the conferences I wanted to join. I talked to burned-out colleagues and hoped to support each other, but I was too burned out to meaningfully make space for others. I dropped all my ‘love’ projects and focused on the ‘career’ projects. But it destroyed me.

I’m now coaching academics, business owners and non-fiction writers to overcome blocks and publish their books and articles. I also am back at Uni as a student, completing an MA in Creative Writing. Step by step, I’m reigniting my joy in writing, human connection, and creativity — which got me into academia in the first place. Now, as a coach, that “empathy/emotion” part of me earns me a living!

Perhaps this article helps you to build a great, sustainable career within the academic system. And if you’re thinking of leaving, here’s a little list of skills I took with me into the ‘real’ world.

The skills of 10 years in academia work elsewhere!

Thanks to the 10 years I spent in academia, I gained massive skills that help me be a writer’s coach today so that I can help others to overcome their struggles and get published faster (and with joy!).

For example, I learned writing skills:

- how to turn data into stories t(hat got into journals)

- turning a ‘mess’ of research into an outline that works

- how to write books, articles, blogs, opinion pieces that build a larger research agenda and align my interests

More importantly, academia trained me to coach authors on:

- how to deal with rejection

- how to overcome procrastination and block

- avoiding burnout

- saying ‘no’ and setting boundaries

But my biggest insight from academia, and my ‘transitioning out’ period, was empowerment and a growth mindset.

For years, I had felt stuck and thought I could never change my identity or make money in any other way than as a lecturer. But burnout and my recovery journey led me to start my own business, earn more than my academic salary, and help hundreds of writers to get published. My identity shifted beyond what I thought was possible.

It was a win, after all.